Major condotel project Cocobay Da Nang made headlines this week as its developer Empire Group announced it will stop paying buyers their annual returns starting next January.

The group chairman Nguyen Duc Thanh told 1,700 buyers that due to financial difficulties, they won’t be able to honor their commitment to pay annual returns of 12 percent on their investment for eight years, leaving many of them burdened with bank debts.

A similar story happened in Nha Trang Town earlier this year. Buyers of Bavico condotel project in the central Vietnam tourism hotspot have taken to the streets with banners many times to protest, demanding the 15 percent annual return on investment that the developer had promised them in 2015. The protests have been in vain, however.

Experts have warned that the unusually high return rates promised by condotel developers sound too good to be true, and they usually are. Nguyen Tran Nam, chairman of the Vietnam Real Estate Association, said at a forum Wednesday that developers who promise returns of 12 percent or more only seek to take advantage of "greedy buyers" who lack knowledge of this type of property.

"I believe that developers who promise high returns have to use money from other projects to pay buyers, as it’s impossible for a condotel project to yield that much profit in the initial period."

For ignoring experts’ warnings years ago, buyers are now suffering. Son, one of the 1,700 buyers of Cocobay Da Nang, paid VND9 billion ($388,000) for a semi-detached house in 2016. But payments from Empire Group have been delayed over the last few months and finding out this week the group will not continue to pay him starting next year was a big blow.

"I owe the bank about 55 percent of the total worth of the house, which is approximately over VND4 billion ($172,400). Excluding principal, interest payments alone come to VND660 million ($28,400) per year."

The problem for condotel buyers like Son is that their situation is worsened by the fact that they are not protected by law. This type of property still does not have a legal framework.

Nam said that although Prime Minister Nguyen Xuan Phuc has ordered ministries to finalize regulations on condotels, there has been no official document providing guidance on dealing with this kind of property even though they have been developed for three years.

This means that ownership of a condotel unit is merely an agreement between a buyer and the developer, and the buyer does not have a pink book, which is the title deed to apartments and houses.

Le Cao, a lawyer with the FDVN law firm, said that the lack of legal framework means that when conflicts happen between buyers and developers, the former could lose in the court as they knowingly took the risk of investing in condotels.

Meanwhile, officials have repeatedly said they are in the process of studying this new type of property. Nguyen Manh Khoi, deputy head of the Ministry of Construction's department of housing management, said that condotel was not residential real estate but a tourism accommodation establishment, like a hotel, and therefore, the Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism should manage it.

"The PM has only tasked the construction ministry with drafting a definition of condotel, such as its size and content, and we are working on this," he said, without giving a deadline.

Meanwhile, buyers are looking at prolonged suffering, if not outright losses.

Like Son, Long, a Hanoi investor who poured VND15 billion ($646,500) into the project, said: "I thought I would receive a stable stream of income from the property, but now I am deep in debt."

Experts said the number of people like Son and Long will increase as Cocobay Da Nang will not be the only failed condotel project.

Troy Griffiths, deputy managing director of real estate consultancy Savills Vietnam, said that as condotel markets in other countries, there will surely be more condotel developers failing to pay buyers the high annual returns promised.

Although condotel remains a potential real estate product in Vietnam, investors could lose their trust in it, he added.

Condotel became popular in Vietnam in 2017 when thousands of units entered the market as the country experienced a tourism boom and demand rose for premium accommodation.

An estimated 27,000-29,000 condotel units came online in 2017-2019, mostly in travel hotspots like Da Nang City, Nha Trang Town, Phu Quoc Island and Quang Ninh Province.

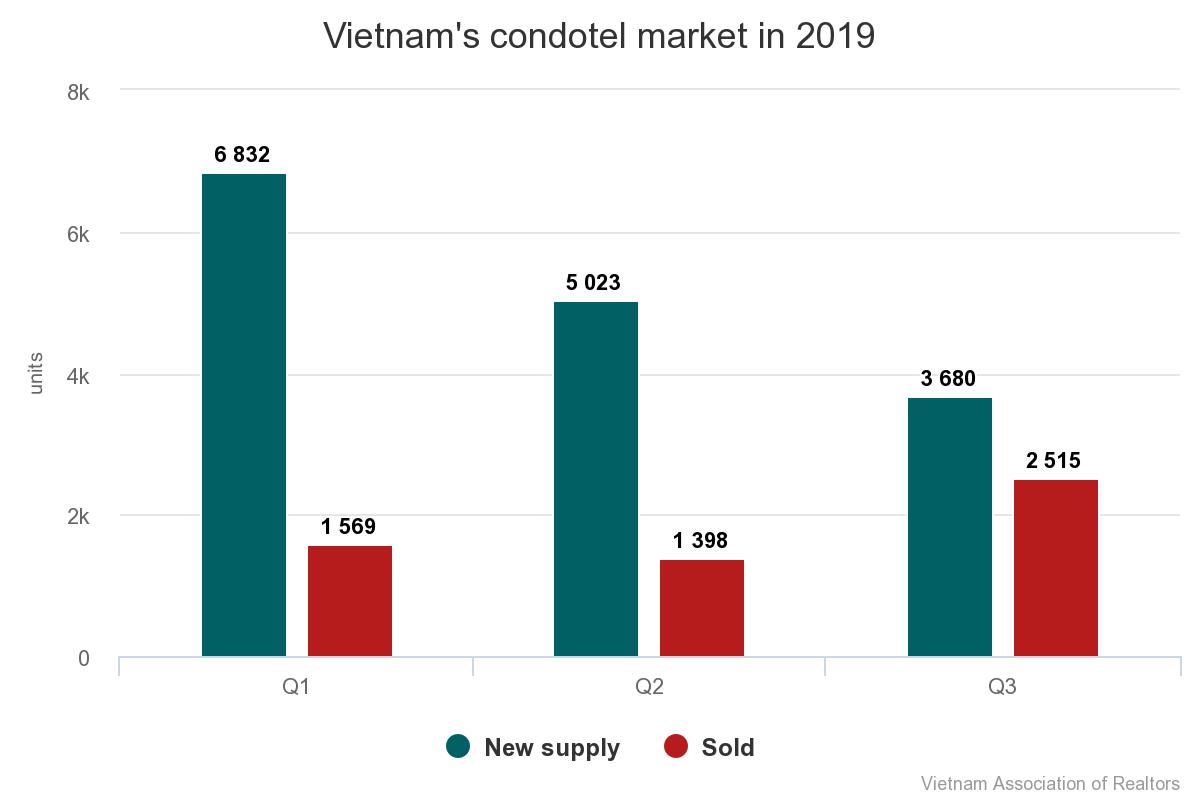

But the lack of a sound legal framework has dampened the market. In the third quarter of this year, 3,680 condotel units came online, 46 percent lower than the first quarter, according to the Vietnam Association of Realtors.

In the first nine months, only 35 percent of new condotel units were bought.